Whether its tracking satellites, developing robotic and engineering solutions or even innovating “space sunnies," Australia has a proud history in providing expertise to lunar explorations.

As the Australian Space Agency enters a new phase of its partnership with NASA to send Roo-ver to the Moon, let's reflect on some of the Australian researchers who made significant contributions to the historic Apollo program since the 1960's.

Dr Phillip K Chapman, Astronaut

The first Australian-born person to be selected as an astronaut was physicist Dr Philip Chapman. He became part of an elite group of 11 scientist-astronauts whom NASA intended at that time to participate in the Apollo Applications Program, which was to have been the follow-on from the initial Apollo lunar landing program. This program would have included ten more Moon landings and three orbiting research laboratories.

Chapman left the astronaut program in 1972 and returned to research, as he did not want to wait for the introduction of the Space Shuttle to make a spaceflight. (The Shuttle did not fly until 1981).

Dr John Colvin, Ophthalmologist

A qualified pilot and consultant ophthalmologist to the Royal Australian Air Force, Dr Colvin had designed spectacles that allowed far-sighted pilots to read instruments, enabling them to continue to meet the visual standards required of military pilots.

His polycarbonate-lens spectacles, which could withstand high gravitational forces, were adopted by NASA for astronaut use. To shield the Apollo astronauts' eyes from the harsh glare of the Sun in interplanetary space, Colvin designed wrap-around, anti-glare sunglasses as well as ‘instrument hood’ glasses intended for use during rendezvous and docking operations to help the astronaut focus on his task.

Professor John Lovering, Geologist

NASA distributed Apollo mission lunar samples to researchers around the world for study. One recipient, Australian geologist John Lovering, at the time Professor of Geology at the University of Melbourne, received Apollo 11 and 12 Moon rock samples.

His chemical analysis revealed a new mineral, tranquillityite, which was later found in samples from every Apollo mission, and a lunar meteorite. Initially thought to be unique to the Moon, tranquillityite has now been found on Earth as well – at several locations in the Pilbara region of Western Australia.

Dr Brian O’Brien, Physicist

As an academic at US universities between 1959 and 1968, Dr O’Brien flew experiments on seven satellites, as well as lecturing astronauts on radiation hazards. He became the Principal Investigator for the Charged Particle Lunar Environment Experiment that would fly on Apollo 13 and 14.

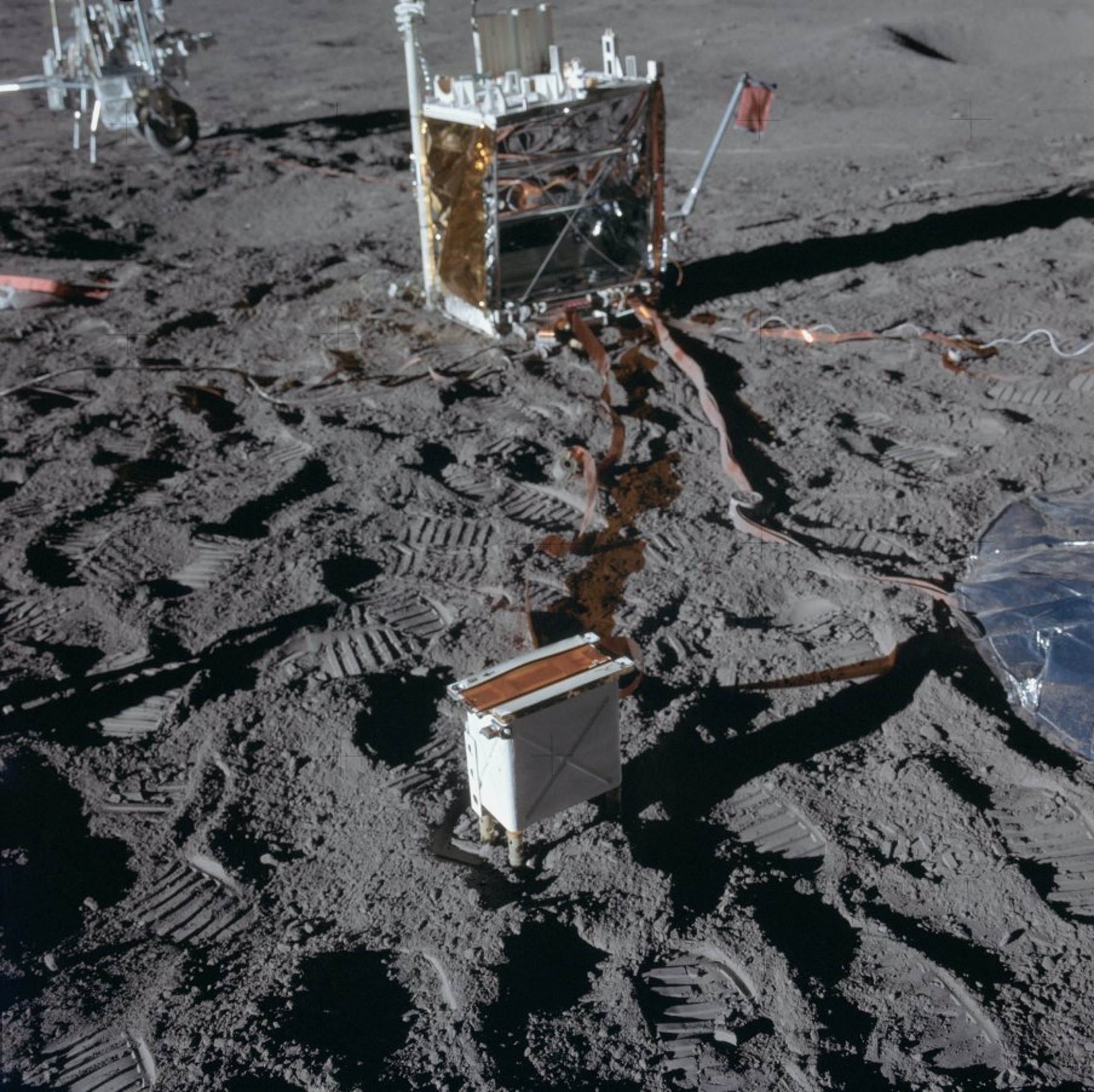

O’Brien believed lunar dust would be a major hazard to astronauts and, in 1966, developed a matchbox-sized dust detector carried on Apollo 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15. His experiments revealed the hazardous impacts fine lunar dust will represent to future lunar operations.

Professor Ross Taylor, Geochemist

Professor Taylor, a researcher at the Australian National University, helped to establish NASA’s Lunar Receiving Laboratory and carried out the first analysis of lunar samples returned to Earth by the crew of Apollo 11.

When the mission’s samples first arrived in Houston, Taylor only had about four hours to complete a preliminary analysis of the rocks as a major press conference was scheduled. He remained a NASA Principal Investigator for lunar samples from 1970 until 1990, working on models for lunar composition and the evolution and origin of the Moon.

Citation for this article

Kerrie Dougherty (2017), 'Australia in space: a history of a nation's involvement', ATF Press: 119-135.

Kerrie currently works at the Australian Space Agency's Space Policy branch as a Senior Heritage and Outreach Officer.

Main image credit: View from the Apollo 11 spacecraft shows the Earth and Australia rising above the Moon's horizon. The lunar terrain pictured is in the area of Smyths Sea on the nearside. All image in this article are courtesy of NASA.